#CentreCourtCentennial

1967: With the Wimbledon Pro event, professional tennis finally comes to the amateur game’s most hallowed lawn

By Jun 17, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

Serena Williams' energetic return to Centre Court after a year away from the game was a brave effort, and one worthy of her legend

By Jun 29, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2009: The first full match under Centre Court's roof showcased British tennis' newest Wimbledon title contender, Andy Murray

By Jun 23, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2008: Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer produced a quantum leap in quality and entertainment in their classic, daylong final

By Jun 22, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2007: After fighting for pay equity at Wimbledon, Venus Williams became the first woman to collect an equal-sized champion’s check

By Jun 21, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1980: The five-set final between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe was the pinnacle of their rivalry—and the Woodstock of their tennis era

By Jun 20, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1975: In defeating a seemingly invincible Jimmy Connors, Arthur Ashe showed that with enough thought and courage, anyone in tennis can be beaten

By Jun 19, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1968: At the first open Wimbledon, Billie Jean King receives her first winner’s check—and notices a “big difference” with her male counterparts

By Jun 18, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1957: “At last! At last!” Althea Gibson fulfilled her destiny at Wimbledon, and with every win she opened up the sport a little wider

By Jun 16, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1937: With a World War looming and one man playing for his life, Don Budge and Baron Gottfried von Cramm stage a Davis Cup decider for the ages

By Jun 15, 20221967: With the Wimbledon Pro event, professional tennis finally comes to the amateur game’s most hallowed lawn

A final between Rod Laver and Ken Rosewall leaves the sellout crowd ready for more, after an eight-man pros-only exhibition event invades the last bastion of amateurism: Centre Court.

Published Jun 17, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

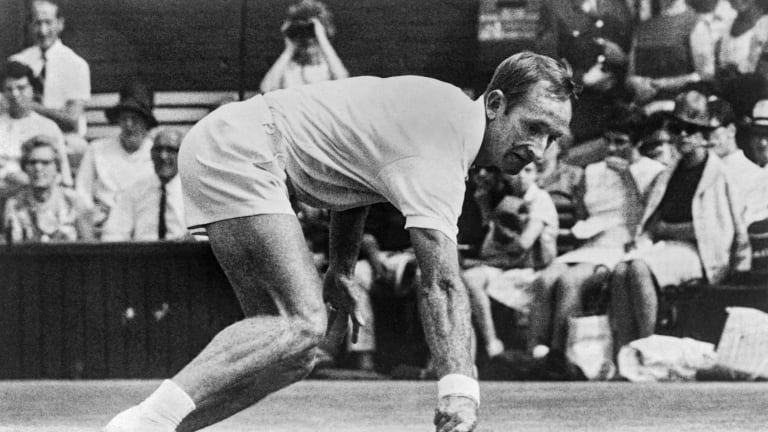

“We couldn’t wait to get back,” Laver said. Five years earlier, when the Rocket announced that he was turning pro, the All England Club had stripped the two-time champion of his honorary membership.

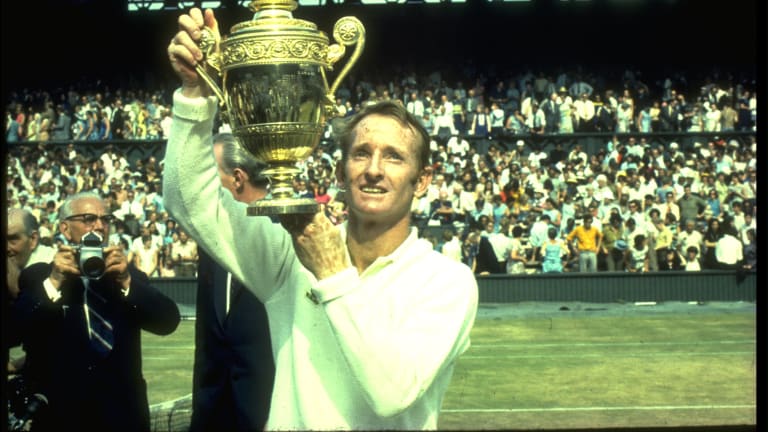

© Getty Images, 1969

Advertising

The tournament ended, appropriately, with the world’s two best players, Laver and Rosewall, facing off in the final. Laver won in relatively one-sided fashion, 6-2, 6-2, 12-10 but the match still far outshone John Newcombe’s easy win in the Wimbledon men’s final earlier that summer.

© AFP via Getty Images, 1968