The Ardent and The Elegant: What Serena Williams and Roger Federer have meant to tennis

By Aug 08, 2022Gallery of Greatness: What Brady, Gretzky, Jordan, Joyner-Kersee, Vergeer and Serena have in common

By Nov 25, 2022How soon could Serena Williams make a comeback?

By Oct 25, 2022The Matches that Made Serena the GOAT: Williams d. Venus Williams, 2017 Australian Open final

By Oct 18, 2022The Matches that Made Serena the GOAT: Williams d. Maria Sharapova, 2012 Olympic gold medal match

By Oct 18, 2022The Matches that Made Serena the GOAT: Williams d. Justine Henin, 2010 Australian Open final

By Oct 15, 2022The Matches that Made Serena the GOAT: Williams d. Martina Hingis, 1999 US Open final

By Oct 13, 2022The Matches that Made Serena the GOAT: Williams d. Steffi Graf, 1999 Indian Wells final

By Oct 13, 2022WATCH: Serena Williams teases “Tom Brady”-style comeback on Good Morning America

By Sep 14, 2022Margaret Court and Serena Williams: A Comparative Discussion

By Sep 13, 2022The Ardent and The Elegant: What Serena Williams and Roger Federer have meant to tennis

Their polar-opposite personalities and playing styles show that there’s no single way to succeed in this solo game.

Published Aug 08, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

Federer and Serena may not end up at the top of the Grand Slam title heap, but together they’ve defined the sport for longer than anyone else in the Open Era.

Advertising

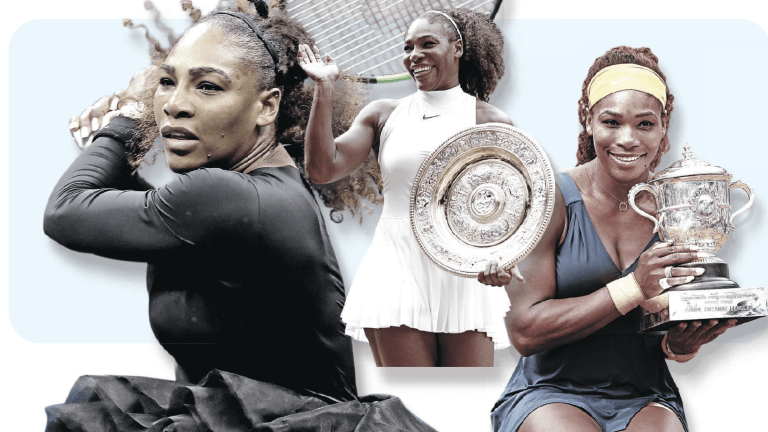

Serena’s blend of talent and tenacity remains unmatched—so it’s no wonder that it turned the sport on its head 20 years ago.

Advertising

Serena’s serve is widely considered to be the greatest shot in women’s tennis history, but her return of serve isn’t far behind. Williams has won each of the four majors at least three times.

Advertising

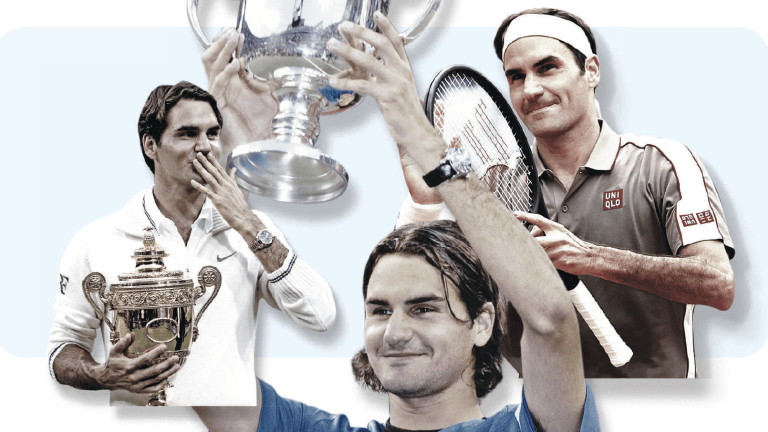

Federer’s Wimbledon win in 2003 seemed to unlock the Swiss on the sport’s grandest stages.

Advertising

Federer’s hair styles and sartorial styles have changed over the years, and so has his game. While many think of it as timeless, that didn’t stop him from upgrading his backhand in his mid-30s.

Advertising

The Ardent and The Elegant, at the 2019 Hopman Cup.

© Getty Images