Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

The Rally: How would a calendar-year Grand Slam by Novak Djokovic compare to similar feats of excellence in other sports?

By Aug 23, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

By the time Novak Djokovic lost the biggest match of his career, he'd already won over the biggest audience of his life

By Sep 13, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

To beat Novak Djokovic, Alexander Zverev said, you need to be perfect. He was right—and one mistake cost him

By Sep 11, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

Six years ago, no one thought Serena Williams would be defeated at the US Open. But along came Roberta Vinci, and down went a calendar-year Slam

By Sep 09, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

Jenson Brooksby and Novak Djokovic gave us a bit of everything. But it was one shot that changed the momentum in the Serb's favor

By Sep 07, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

Novak Djokovic is searching for a Grand Slam, and a little love, at the US Open

By Sep 05, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

Griekspoor, heckler no match for Novak Djokovic, now five wins away from completing calendar-year Slam at US Open

By Sep 03, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

Holger Rune has his moment, but Novak Djokovic wins in four sets, leaving him six wins away from tennis history

By Sep 01, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

A timeline of Novak Djokovic's path to ultimate greatness

By Aug 29, 2021Novak in NYC: '21 Slam, 21 Majors?

Like a fine gluten-free wine, Novak Djokovic seems to only get better with age

By Aug 27, 2021The Rally: How would a calendar-year Grand Slam by Novak Djokovic compare to similar feats of excellence in other sports?

And how would it stack up against Rod Laver’s Slam from 1969?

Published Aug 23, 2021

Advertising

Advertising

Advertising

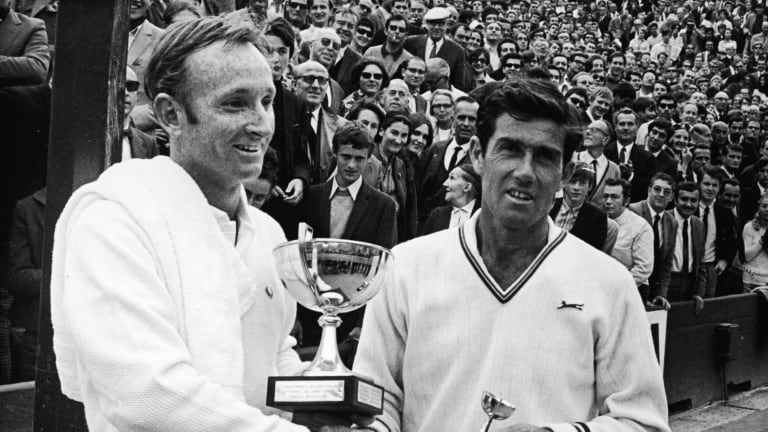

Laver after defeating Rosewall in the 1969 French Open final.

© Getty Images

Advertising

Advertising

Djokovic will face emboldened opponents and enormous pressure at the US Open—a Grand Slam tournament he's won "only" three times.

© 2018 Getty Images