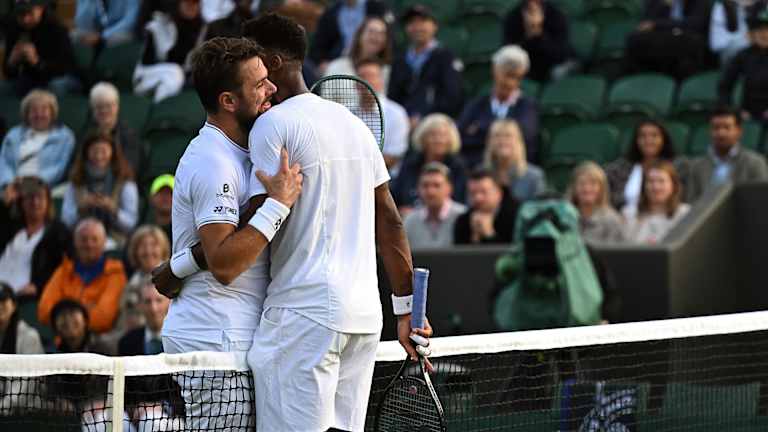

LONDON – As a Wednesday night second-round match between Gael Monfils and Stan Wawrinka sprinted to its conclusion on Thursday afternoon, as these two veterans engaged in one multi-layered all-court rally after another on Wimbledon’s Court 2, one word came to mind: inspiration. The inspiration to excel. The inspiration to perform. The inspiration to play.

The Wawrinka-Monfils match had been suspended last night shortly after 9:20 p.m., with Monfils leading two sets to love and Wawrinka poised to serve at 5-all in the third. The two resumed at nearly 3:00 this afternoon. Following a Wawrinka hold, Monfils took 11 of the last 14 points, closing out a 7-6 (5), 6-4, 7-6 (3) victory with a feathery forehand drop shot. All told, the match lasted three minutes past the two-hour mark.

Read More: Is Alejandro Tabilo tennis' most underrated versatile player?

Wawrinka is 39 years old; Monfils is 37. So what if each is past his prime? What mattered over the course of this two-day match was the chance to see two thoroughly experienced athletes relish the chance to reveal themselves and engage with one another in the simple yet powerful medium of competition.

At this stage of their careers, the circle of time completes. Once, there was a young boy who lived for the chance to hit tennis balls and throw himself into battle. Then came year after year in pursuit of results and the physical and mental challenges of a highly competitive, global solo effort. Now, as the end nears, tennis is once again less about labor and more about the joy felt by that child.

Afterwards, when I asked Monfils what he continues to enjoy about playing at venues like Wimbledon, he told me, “I love the competition. I love the sport. I love the game... it's a feeling that you can't have anywhere else.”